Tulip Bulb Mania is a widely regarded financial phenomena, but the discussion of what historians think actually happened is fiercely debated. This article will discuss the history of Tulip Bulb Mania, elaborate on how it began, detail what historians believe actually happened, and explore the influence it had on the Dutch economy

What Was Tulip Bulb Mania?

Throughout the 17th century, the Dutch were considered one of the top financial and economic forces in the world. Tulip bulbs had recently been introduced to the Dutch and quickly became a symbol of status and fashion. Tulip mania occurred during what is called the Dutch Golden Age. This affluent country had the highest per capita income in the world from approximately 1600-1720.

The Dutch society was unique in that it possessed a mercantile middle and lower class. This was unique because it didn’t exist in such advanced form anywhere else in European history. The Dutch middle and lower class began striving to resemble their wealthier neighbors, meaning they also wanted to own tulips.

Formally organized futures markets were first established in the Dutch Republic in the 17th century. In 1636, the tulip trade had become so popular that marketplaces were formed on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, Haarlem, Rotterdam, and more. Tulip futures were among some of the most noteworthy, particularly during the peak of tulip mania.

The Start of the Bubble

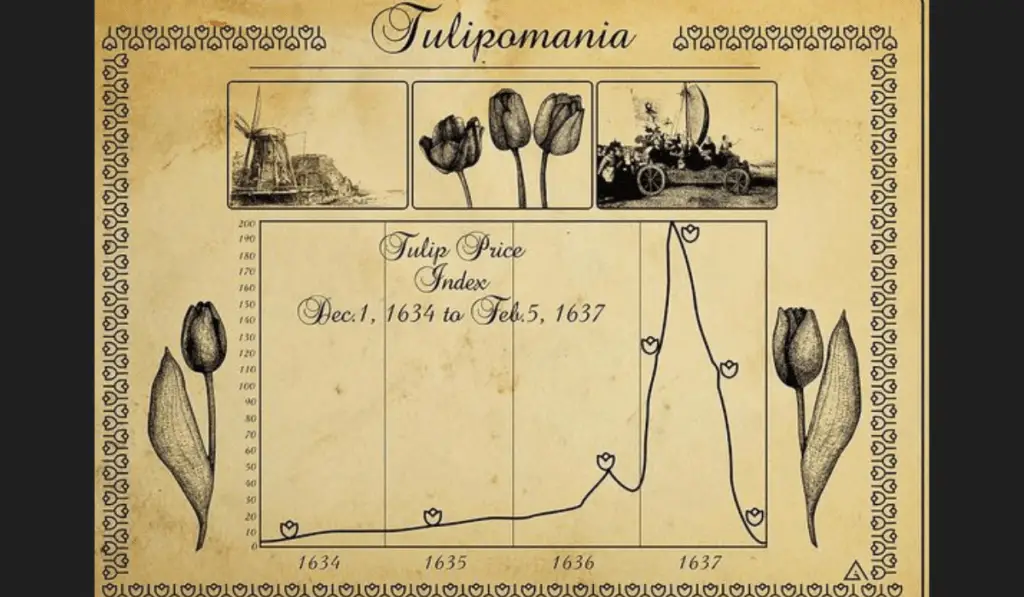

The Tulip Bubble started ballooning when selling prices for certain bulbs hit exceptionally high rates. At the height of the tulip craze, individual bulbs were said to have sold for more than ten times the annual salary of a skilled artisan at that time. This price surge ramped up in 1634, then collapsed in February 1637.

The limited trading logs from the 1630s, many originating from biased sources, make research on the tulip bubble challenging. Many economists have given more practical reasons for the rise and fall of tulip bulb prices instead of speculative frenzy. One explanation is that other flowers also started out having high prices which later fell as the flowers were propagated.

At the time, the tulip frenzy was viewed as a financial and cultural phenomenon, but not a severe economic disaster. It’s typically viewed as the very first recorded asset bubble in history. “Tulip mania” is now used as a metaphorical term to represent a major economic bubble where asset prices are drastically higher than the inherent value of the physical item.

How Did Tulip Bulbs Arrive in Europe? [The Start of Tulip Mania]

Tulips arrived in Vienna in the 16th century via spice trade networks and were quickly distributed throughout the rest of Europe. These imported blooms had a feeling of exoticism that was unlike any other flowers indigenous to the region. This then-exotic flower differed from anything in Europe at that time due to the intensely saturated colors of its petals.

Recommended Reading: The History of Options Trading – How Options Trading Started

These beautiful flowers quickly rose in popularity, becoming a symbol for taste, status, and beauty that only the wealthy could afford. The wealthy were acquiring tulips just to show they were wealthy enough to afford tulips.

Tulips were a famously delicate flower that would quickly wither and die if not expertly cultivated. Professional tulip cultivators became more effective and prosperous at growing the flowers domestically in the 1600s, which generated a thriving commercial sector that has been maintained to this day.

The Dutch discovered two methods for growing tulips: from seed or from buds that grew on parent bulbs. They learned that bulbs could bloom the following year, while seedlings could take up to 7-12 years to bloom.

The tulip craze also became about owning rare strains of the flower. Tulip traders were particularly interested in broken bulbs, which were tulips with a striped, multicolor appearance instead of one solid color. This unpredictable variation was another driving force in the rise of tulip prices. Some of the highest cited prices for tulips during the height of tulip mania were for these rare broken bulbs.

What is a Dutch Florin? [The Cost of The Tulip Bubble]

A Dutch florin was the currency of the Netherlands from the 1400s until the 2000s. The Euro replaced the Dutch florin in 2002. Florins were gold coins of varying quality and weight, which makes estimating their current monetary value difficult.

Tulip Mania raged through the Netherlands in 1634 as the Dutch feverishly acquired tulip bulbs. Typical spending habits were disregarded as even some of the poorest Dutch citizens participated in the tulip business. It’s estimated that an individual bulb may have been valued at 4,000-5,500 florins.

It seemed like everyone was gaining wealth simply by owning a few of these unusual bulbs. As the value of tulips continued to rise, It may have seemed like tulip mania would go on for an extended period of time. This hope was soon destroyed.

The Tulip Bulb Bubble Crash

Prices began to plummet by the end of 1637 and just never recovered. A substantial part of this quick fall was caused by consumers purchasing bulbs on debt in the hope of repaying their creditors when they liquidated their tulip bulbs for a premium. However, as prices began to fall, owners were obliged to sell the bulbs at whatever price they could get from them. This forced many to claim bankruptcy.

Buyers claimed that they would not be able to pay the exorbitant price set upon for the tulip bulbs, and the bubble popped. One of the biggest challenges after the tulip bubble popped was settling the hundreds of contested purchases. These cases were taken to the Court of Holland, which forced each city to put a stop on its tulip contracts and solve each individual case according to their own best judgment.

The city of Haarlem took the longest to resolve each tulip contract. It left disgruntled parties to settle their debts via arbitrators or other methods. While some bulb growers were adamant they be paid in full, agreements were finally made for amounts that buyers could actually afford.

How Did Tulip Mania Impact the Economy?

Although tulip mania was not a catastrophic event for the Dutch economy, it did damage societal expectations. When the bubble finally popped, it destroyed the relationships between certain consumers and sellers, along with people’s willingness and ability to pay their debts. Debt defaults generated cultural shock in an economy reliant on relationships and complex credit arrangements.

The effects on the Dutch economy when the tulip bubble burst were minimal. The bulb trade was a minor component of the economy. Since trading tulip bulbs was a side business for most florists, bankruptcy and suspensions were rare. Despite losing out on additional income from selling high-priced tulip bulbs, the growers’ sales and debts ended up canceling each other out.

The majority of financing used throughout the bulb marketplace originated from interested parties involved in bulb transactions instead of traditional financial institutions. As a result, the economic loss in the bulb sector was confined, and banking institutions were not harmed. The Netherlands’ payments and loan system remained steady. This dispersed issue did not damage the entire economy, and the whole occurrence was brief and confined.

Conclusion

While tulip mania is a historical financial occurrence typically regarded with reverence and intrigue, it actually wasn’t as detrimental to the Dutch economy as we once thought it was. Even though tulip bulbs cost ten times more than an artisan’s yearly salary during the height of tulip mania, new historical data keeps emerging that changes our understanding of this phenomenon. One thing we can all agree on is that we’ll never look at a tulip the same way again!